Molly Ockett and Her World

|

The following

material is excerpted from an exhibition that was on view at the

Bethel

Historical Society from July 2004

through May 2007

|

|

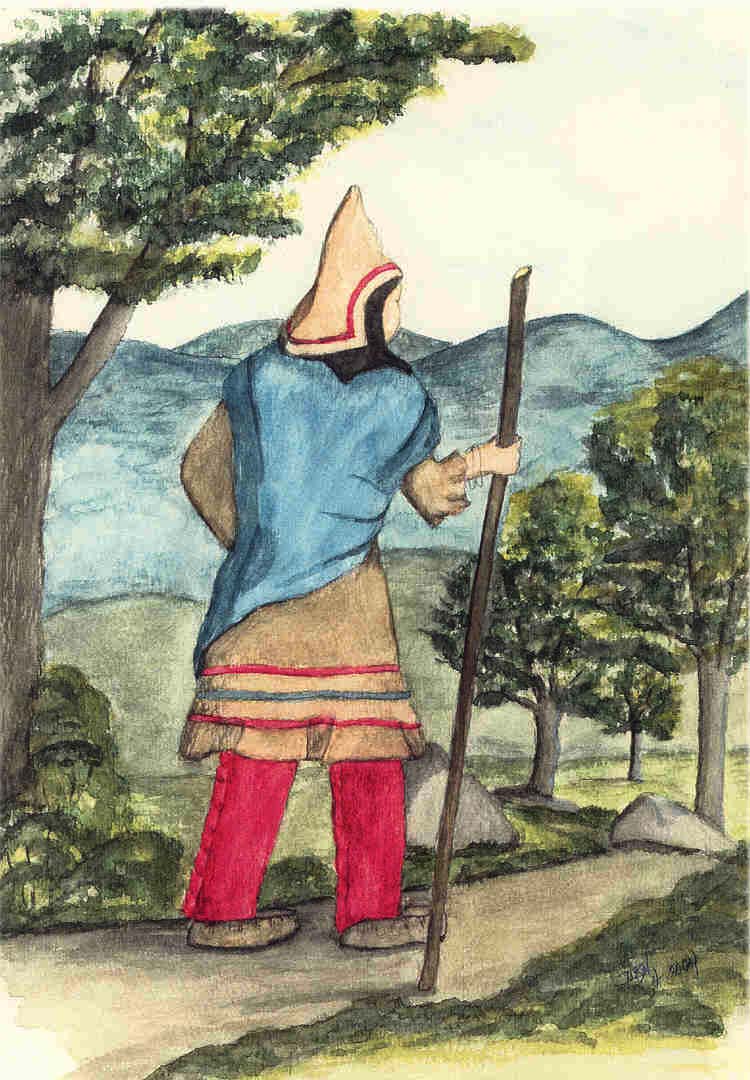

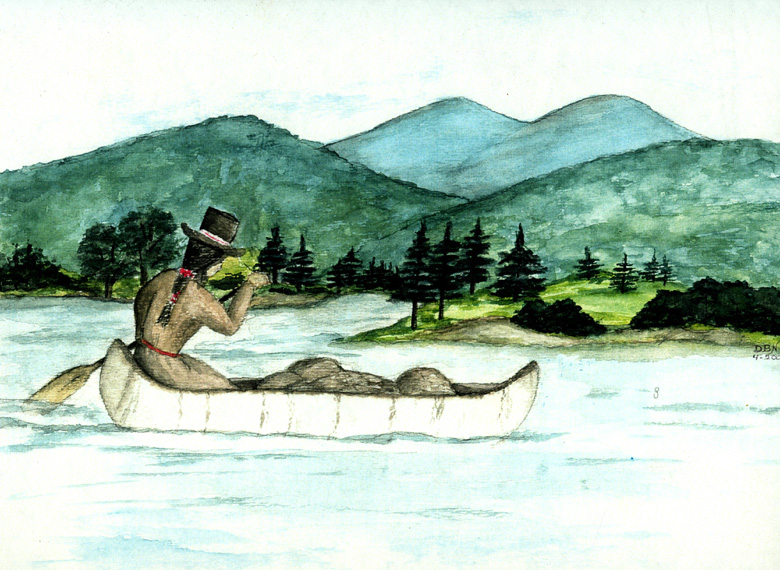

Introduction IntroductionThis exhibit tells the story of Molly Ockett, an Abenaki Indian of the Pigwacket tribe whose lifetime (ca. 1740-1816) spans an important and particularly tumultuous period in this region's past. Born at Saco, Maine, Molly Ockett—baptized "Marie Agathe"—is one of the best-known individuals from the local past in the mind of the average resident of western Maine. As an itinerant healer and herbalist for both natives and newcomers, Molly Ockett established close relations with the early settlers in such communities as Andover, Fryeburg, Poland, Paris, and Bethel during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Such ties enabled her to gain an intimate view of white society as it spread throughout the vast wooded domain long occupied by her ancestors. Since her death in 1816, Molly Ockett has become a legendary figure, the subject of fireside story-telling, of school pageants, and of popular magazine articles, many of which contain inaccurate information. Renowned as "the last of the Pigwackets," she is honored annually at Bethel's "Molly Ockett Day" celebration, and her name is connected with numerous geographic landmarks, business ventures, and community organizations. Molly Ockett's place in the consciousness of this region has been ensured by a certain "Indian mystique," complete with romance, curses, buried treasure, and near-miraculous cures. But what of the real Molly Ockett? By focusing on the most reliable information available about her life, this exhibit raises this Native American woman from the realm of myth and legend to the status of a documented personality in the colonial history of the northern New England frontier—a place that was truly Molly Ockett's world. Painting by Danna Brown Nickerson |

|

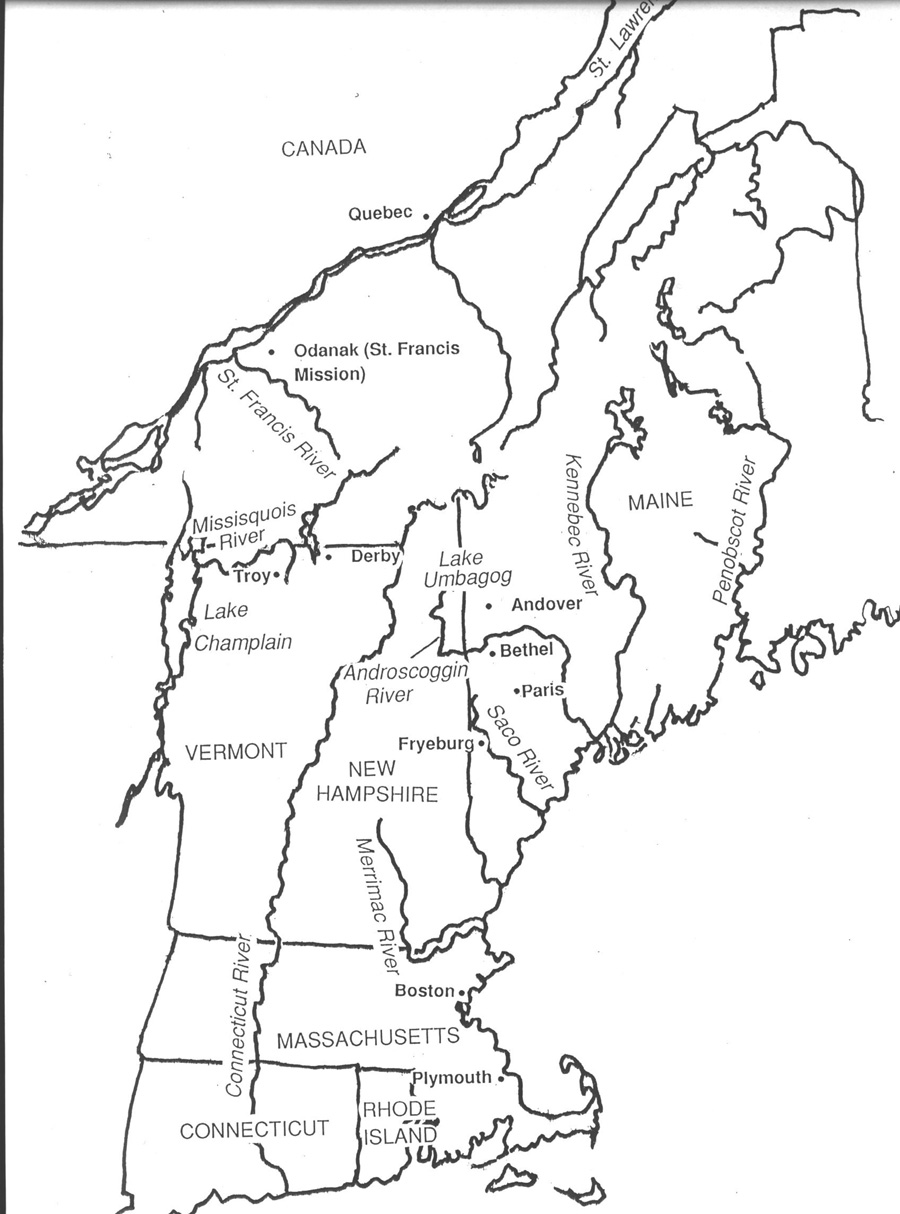

| Background In the centuries before Molly Ockett's birth around 1740, the Abenaki, an eastern Algonquian sub-group, maintained their historic homeland over an area stretching from the Iroquoian tribal lands in southern Québec to the northern Massachusetts border and from the Passamaquoddy territory in eastern Maine to the shore of Lake Champlain in western Vermont. Translated as "people of the Dawnland" or "eastern people," the Abenaki were composed of numerous bands of Native Americans historically identified by the names of the river valleys, or principal villages, in which they lived at the time of European contact. Molly Ockett was a member of the Pigwackets, who occupied the Saco River Valley and environs, and whose main village was situated on a plateau above the Saco intervales at present-day Fryeburg, Maine—some forty miles south of Bethel and a short distance east of the present border between Maine and New Hampshire. Among those Indians with whom the Pigwackets would have had close communication were the Pennacooks of the upper Merrimack and Pemigewasset River valleys, the Sokokis and Coosaukes of the upper Connecticut and Ammonoosuc watersheds, and the Amarascoggins, who resided in the Androscoggin River valley. Data is lacking for a reliable estimate of Abenaki populations before 1600, but it is reasonable to state that in that year several thousand individuals inhabited the White Mountain region of Maine and New Hampshire, with a total population in New England as a whole of well over 100,000 native people. Interrelated through marriage, and sharing a common dialect, the Abenaki participated in an annual cycle of migration that took them southward to seashore camps for the summer, northward to deep woods hunting camps in the winter, and back to their riverside villages for late fall feasting and spring fishing and planting. By the middle of the 17th century, the traditional Indian way of life in this region was undergoing drastic change. An attitude of friendly curiosity turned to distrust and hostility as the native population watched their numbers rapidly dwindle due to virulent epidemics introduced by Europeans. Indian intertribal relationships disintegrated due to the burgeoning fur trade and the introduction of firearms. The demand for furs, especially, strained the native economy by using up time previously spent in search of large game for food and skins; the fur trade also made natives much more aware of the importance of territorial boundaries, a concept foreign to the Abenaki before European notions of private land use and ownership were imposed on the region. The intermingling of cultures was further strained by the effects of the liquor trade, a significant component in English and French efforts to maintain Abenaki allegiances as the century wore on. Molly Ockett entered the world in a period when her people faced ongoing and violent frontier warfare from a succession of colonial conflicts between French Canadian colonists in the St. Lawrence Valley and Protestant New Englanders on the Atlantic seaboard. Caught in the middle, the Abenaki were forced to choose sides, with many retreating to Indian mission villages in Canada where they stayed between long, seasonal hunting and fishing forays in their old territories to the south. Following the loss of Canada by the French in 1763, English settlements spread northward into interior Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, in relative security. Some of the Indians who had withdrawn to Canada, including a number residing at the Québec missionary village of Odanak on the St. Francis River, returned to the Saco and Androscoggin valleys where they interacted with the white settlers in a spirit of accommodation. Anxious to remain in their ancient homelands, these individuals were tested again during the American Revolution, when they found themselves split in allegiance between the colonists and the English. Following that conflict, a small number of Abenaki stayed in the vicinity, becoming absorbed into the white way of life through inter-marriage or by assuming the role of guides, craftsmen, or, as in Molly Ockett's case, medical practitioners and advisors to the white newcomers. |

|

|

King Philip's War

(1675-1676), a brief but bloody conflict between Native Americans and

English colonists in southern New England, marked a turning point in

17th century encounters between Indians and Europeans. However,

it was not the worst disaster to occur during a long period of tension

and upheaval. That honor goes to the "Great Dying," a cataclysmic

scourge brought upon the native population by epidemics—notably

smallpox, measles, and typhus—from which they had no immunity.

Spreading into this region from the mouth of the Saco River in 1617 and

up the Connecticut River by 1635, these contagious diseases seriously

reduced Abenaki numbers, perhaps by as much as 90 percent. |

|

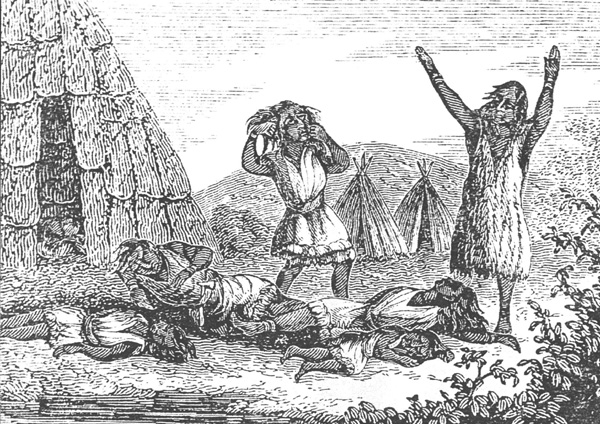

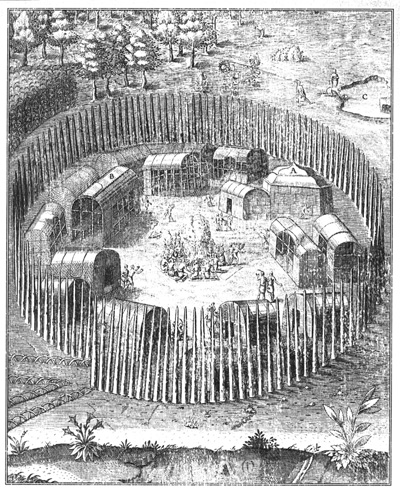

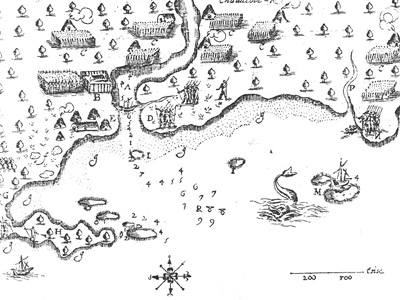

A major focal point

of Molly Ockett's world was Pigwacket, the ancient Indian enclave at

present-day Fryeburg, Maine. This late 16th century

representation of an East Coast Algonquian village conveys something of

Pigwacket's appearance in the decades before Molly Ockett's

birth. A description of the semi-abandoned Pigwacket village made

in 1703

by an English scouting party led by Major Winthrop Hilton states: "When

we came to the fort, we found about an acre of ground, taken in with

timber [palisaded], set in the ground in a circular form with ports

[gates], and about one hundred wigwams therein; but had been deserted

about six weekes, as we judged by the opening of their barnes [storage

pits] where their corn was lodged." The bark-covered wigwams or

longhouses in this view (excepting "A") are typical of Abenaki

dwellings used in this region. By tradition, "Pigwacket" is said

to mean "at the cleared place." |

|

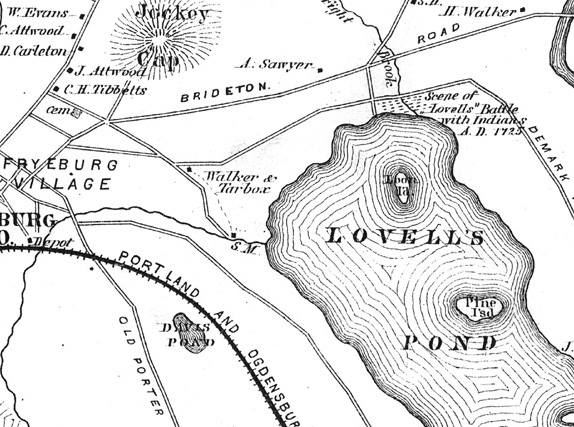

The village of

Pigwacket was the scene of one of the most widely known military events

in colonial New England history when, on May 8, 1725, thirty-four

English scalp hunters led by the daring Captain John Lovewell engaged

some forty Abenaki led by the Pigwacket chief Paugus. The ensuing

"Battle" resulted in heavy

casualties on both sides, including Lovewell and nineteen of his

compatriots, as well as Paugus and an equal number of his

followers. A major result of this legendary skirmish was a

general shift in the remaining Abenaki population in this region to the

north and east, away from entanglements of the English-French rivalry. |

|

A monument

commemorating the "Battle of Lovewell's Pond" was erected at Fryeburg

in 1904 by the Society of Colonial Wars. The monument's plaque

states, "To mark the field of Lovewell's Fight on the 8th day of May

1725 between a company of Massachusetts Rangers of 34 men and 80

warriors of the Pequawket tribe led by Paugus in a contest lasting from

early morning until after sunset / The Indians were repulsed and their

chief killed." No mention is made on the monument of the many

centuries the Abenaki had peacefully occupied this place before it was

"discovered" by Europeans. |

| Birth and Early Life Certain experiences during Molly Ockett's childhood and young womanhood provided a firm foundation for her future role as a bridge between the worlds of the Abenaki and the white settlers. Although born around 1740 at Saco, Maine, Molly Ockett doubtless spent her earliest years sixty miles upriver at Fryeburg, where, according to the historian Dr. Nathaniel T. True, "she was wont to say that she could remember when the pine trees on the plains . . . were not taller than herself." During King George's War (1744-1748), she and other Pigwackets gambled on a political alliance with the British and removed to a coastal location in Plymouth County, Massachusetts, where Molly Ockett no doubt learned to speak English and became acquainted with Protestantism—giving her an advantage over her fellow tribespeople, most of whom knew only Catholic religious rituals and spoke some French but no English. Between 1750 and 1755, when the so-called "French and Indian War" erupted, Molly Ockett and her kin-group returned to their seasonal movements, apparently living for extended periods at Narankamigouak ("Rockomeka" to English ears), a fortified Abenaki village on the Androscoggin River at Canton Point, some forty miles downriver from Bethel. Situated a relatively safe distance from English settlements, this former mission village was only a two-day portage from the Indian community at Norridgewock, where the nearest Jesuit priest then resided. After the outbreak of the French and Indian War, English authorities initiated a campaign to rid northern New England of the Abenaki once and for all. Utilizing methods that today would be characterized as "ethnic cleansing," the English increased the bounty on Indian scalps to as much as three hundred pounds each and sent troops upriver to destroy individuals and encampments, regardless of their position toward the English. Facing such odds, Molly Ockett's remnant band joined the Abenaki exodus to Canada, where they gathered with others at the St. Francis mission of Odanak in Québec. The 1759 fall of Québec and the burning of Odanak that same year by Major Robert Rogers and his Rangers signaled a turning point in Molly Ockett's life. Nearly twenty years old at the time, Molly Ockett was at Odanak during that horrific event and barely escaped by hiding behind a bush. With the 1763 Treaty of Paris, the French were effectively eliminated as a political force in Canada, thus allowing the growing English colonial population to the south to spread inland, unfettered by threats from the north or the relatively small number of Abenaki remaining in the region. Their numbers depleted by war and pestilence, the surviving Indians cautiously returned to something resembling their old seasonal patterns of travel, albeit without the support of their former allies in French Canada. For those, like Molly Ockett, who chose to return to their ancestral homelands, a very different world awaited them. "Marie Agathe" Becomes "Molly Ockett" The 18th century intermingling of Indian and white cultures is well-illustrated in the matter of Indian names, a later problem for scholars searching for references to Molly Ockett in records made during her lifetime. Many Abenaki Indians in this region were Catholic and received Christian names at baptism from French Catholic missionaries. These names were used by the Indians in communicating with the English and were written phonetically from the Indian pronunciation, emerging in a new form. In some instances, given names were assumed to be surnames, compounding the confusion. Thus Marie Agathe, which sounded with French pronunciation like "Mari Agat," became "Mali Agit" when spoken by the Abenaki, who had difficulty coping with the "r" sound. To English ears, Mali Agit sounded like "Molly Ockett," resulting in the name so thoroughly familiar to residents of this region today. Among the names and spellings used over the years for this individual are the following: Marie Agathe, Mari Agat, Mareagit, Mali Agit, Molly Ockett, Mollyocket, Mollyockett, Molly Occut, Mollocket, Mollockett, Molly Lockett, Moll Lockett, Molly Orcutt, Moll Ockett, Molley Ockett, and Mollywocket. |

|

|

Like other Native

Americans inhabiting northern New England, the Pigwackets were a

semi-nomadic people, moving easily up and down river in light birchbark

canoes in pursuit of sustenance. This 1613 map of Saco, Maine, by

Samuel de Champlain includes Abenaki wigwams, longhouses, and

cornfields used by the Pigwackets each spring when they left their

winter hunting districts near Fryeburg to gather shellfish and other

foods on the Atlantic shore. By her own account, Molly Ockett was

born around 1740 on a point of land below the falls at Saco during one

of these coastal sojourns. |

|

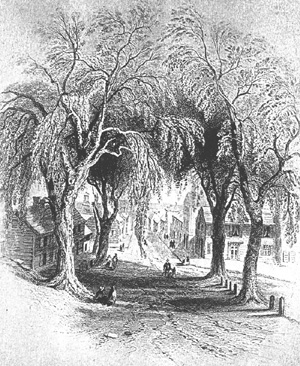

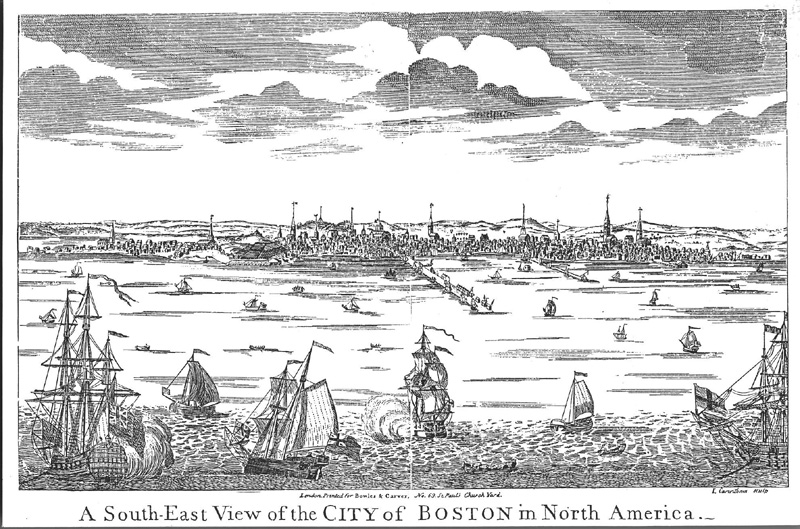

During King George's

War, a handful of Pigwacket men volunteered to fight for the English in

exchange for protection for their families. In June of 1744, the

Pigwacket chieftains Saquant and Weranmanhead (one of whom may have

been Molly Ockett's father), with sixteen women and children—including

a girl named "Mareagit"—arrived at Saco

Falls. Eventually, these

Indian families were taken to Weymouth, Massachusetts, and then to a

nearby coastal location in Plymouth County, where they remained,

"provided for by order of government" for about four years.

Following the cessation of hostilities, the Pigwacket families, except

for three unwilling young girls, were returned to Maine to be present

at peace treaty negotiations at Falmouth in 1749. Among the three

recalcitrant girls was Mareagit, who by now was used to English ways

and was no doubt uneasy about leaving the Boston area (an early view of

Leyden Street in Plymouth is shown here). Nevertheless, she and

the other two girls were brought back to Maine, arriving at Fort

Richmond on the Lower Kennebec aboard an English sloop in the spring of

1750. |

|

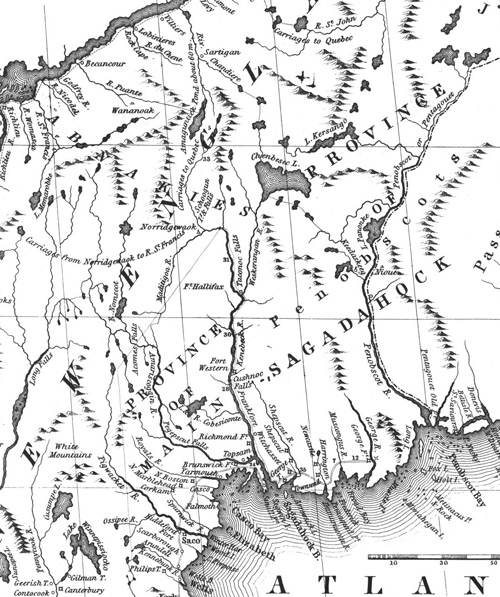

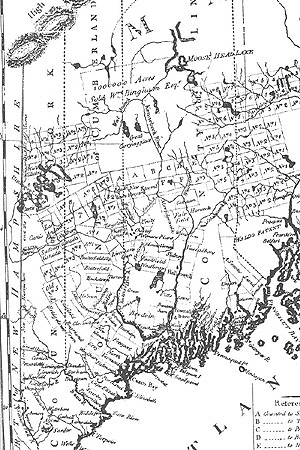

In this detail from

John Mitchell's 1755 Map of the

British and French Dominions in North

America, we have an intimate view of Molly Ockett's world at the

outbreak of the so-called French and Indian War (1755-59), when many

Abenaki found safe haven at the Canadian mission village of Odanak on

the St. Francis River. Note the "Pigwacket R[iver]"

at the bottom left, a major focal point in the lives of generations of

Molly Ockett's ancestors. This map, used in the peace

negotiations ending the American Revolution, identifies numerous

English forts and settlements along what is now Maine's southern and

central coast. |

|

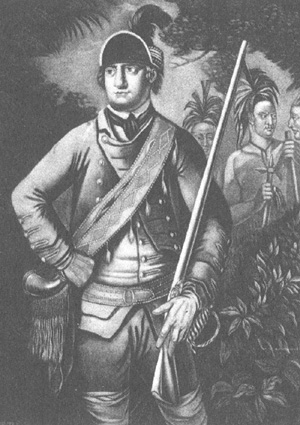

Known to the Abenaki

as "the White Devil," Major Robert Rogers of the British Army was

ordered to neutralize New France's Native allies in 1759. Showing

little mercy, Rogers and his Rangers destroyed Odanak (or

"Arasagunticook," as it was then called), the main Abenaki village in

the

St. Lawrence River Valley, killing many of its residents and burning

most of its buildings, including the church. Molly Ockett

witnessed the attack by Rogers' men and survived by secreting herself

in some bushes nearby. |

| Dispossession

and Accommodation The permanent colonial settlement of the "eastern slope" of the White Mountain region—the heart of Molly Ockett's world—began in the early 1760s at Fryeburg and followed an arrangement common to much of northern New England in the years just before and during the American Revolution. Unlike in earlier days, when provincial governments granted townships to settlers who also acted as "proprietors" (owning home lots clustered in villages and holding pasture land and woodlots in common with other shareholders), many of the earliest towns in this vicinity were granted to people of influence who had little, if any, interest in relocating to the North Country. These absentee landlords, some of whom received grants as payment for military service during the French and Indian wars, hired surveyors to create town plans divided into grid patterns of roughly 50-acre parcels that did not call for a centralized village and which virtually ignored the local topography. During the 1760s, a handful of white settlers, anxious to take advantage of the agricultural, forest, and mineral wealth of this newly-opened territory, purchased farmsteads from these town proprietors or, in some cases, were given land in an effort to meet certain grant stipulations. "Gateway" towns like Fryeburg, Maine, and Conway, New Hampshire, were hurriedly established, and within a few years the pace of land granting quickened, so that before the outbreak of the American Revolution, most of the towns in this area had been laid out and mapped, though some had yet to see land cleared for farmsteads. The emigration of people into this region from the south was slowed but not halted by the Revolution. Far removed from the panic and confusion in New England's older communities, these emerging backwoods settlements were relatively safe from British reprisals. Numerous stories handed down by descendants of the first white settlers tell of how their most frequent visitors during the coldest months were the Abenaki, some coming from St. Francis and all of whom were struggling to retain a measure of their traditional culture, despite being dominated by an ever-growing English population. Camping seasonally in bark wigwams near Fryeburg and other frontier settlements, these native people, including Molly Ockett, survived by hunting, fishing, and trading furs and homemade crafts and cures to the white residents. Part of a small ethnic minority numbering only in the hundreds, Molly Ockett made use of her special skills and vast medicinal knowledge to forge important and useful relationships with these newcomers—links that served her well throughout the remainder of her life. |

|

|

Molly Ockett and

others of her kin-group were in the Bethel area in the mid-1760s and

witnessed the clearing of land and the construction of houses as white

people arrived to usurp the former Abenaki territory. The

civilizing tendencies of these pioneers are well conveyed in this early

19th century depiction of Oxford County's "shire town" at Paris Hill

village, some twenty miles south of Bethel.

View

of Paris Hill, 1802. Oil on pine board, 30" x 48", artist

unknown. An over-mantel painting from the Lazarus Hathaway House,

Paris Hill. Gift of Miss Mabel Hathaway to Hamlin Memorial

Library, 1957. Courtesy of Hamlin Memorial Library |

|

Abenaki survival in post-Revolutionary Maine (delineated here in a 1795 map by Osgood Carleton), as well as other parts of northern New England, depended on accommodation to the white man's world. Often camping near the newly laid out communities for months at a time, Indians continued to visit and travel throughout the region well into the 19th century. Bethel historian Dr. Nathaniel T. True, writing in 1859, stated, "It was no uncommon sight for quite a fleet of boats [canoes] to pass up and down the river in company." Sudbury Canada, now Bethel, appears just to the right of the "m" in "New Hampshire." |

|

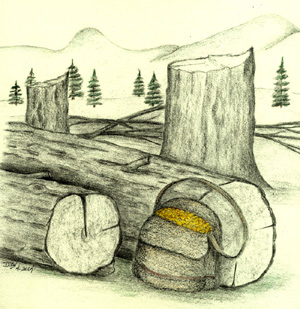

The first white

settlers to venture into this region discovered something the Abenaki

had known for generations: the level "intervales" alongside the

Androscoggin and other rivers contained amazingly fertile soils that

were ideal

for raising a variety of crops, most especially corn. Indian

"cellars" for storing corn and other provisions were found near

Bethel's Riverside Cemetery when the "Mayville" section of the town was

opened up to

farming in the 1770s. Courtesy

of Stanley R. Howe |

|

Despite her

familiarity with the ways of the white settlers, Molly Ockett practiced

an Indian style of living during her travels throughout the area,

including trips to northern Vermont, New Hampshire, and

Canada. Stopping at favorite campsites and sharing meals at

the home of special friends, Molly Ockett preferred to dwell in

bark-covered wigwams made of tall saplings enclosing a space about 15

feet in diameter. |

| The

Many Faces

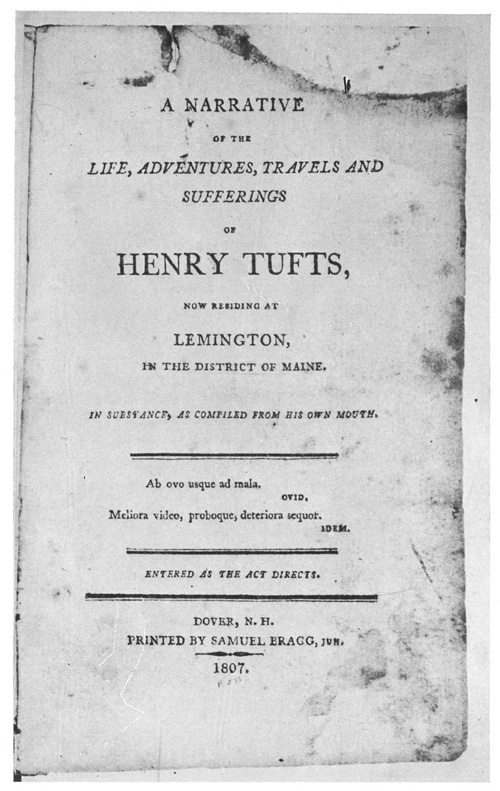

of Molly Ockett Molly Ockett died in 1816, well before the invention of photography, but 19th century accounts describing her habits, activities, beliefs and physical characteristics reveal important clues to Molly Ockett's many "faces." Among the earliest of these descriptions (see below) is one published in 1807 that gives us a rare glimpse of Molly Ockett's life in the 1770s when she had a brief association with Henry Tufts, a shady character who traveled about traditional Abenaki territory for several years during that time. A later but equally valuable recounting of her life, based on the recollections of those who knew her, was authored by Dr. Nathaniel T. True and appeared in the |

|

|

Physical

Appearance and Dress Molly Ockett was described by her contemporaries as an impressive woman, a woman possessed of "a large frame and features" and an erect carriage, even in old age. When allusion was made to this latter trait, Molly Ockett would remark, "We read, straight is the gate." She wore clothing typical of Abenaki women of her day: a knee-length European-style dress, leggings embroidered with dyed porcupine quills, beaded moccasins, and, during the colder months, a peaked cap decorated with colored beads. Aspects of her personality appear to have impressed white acquaintances as much as her physical presence. Ninety-year-old Martha Rowe of Gilead, Maine, in an interview with Dr. Nathaniel T. True in 1861, told of how she knew Molly Ockett as early as 1779, describing her as "a pretty, genteel squaw." Undoubtedly, Molly Ockett's "erect" posture made her stand out among other Abenaki of her day, but it was her proficiency with the English language, out-going personality, and expertise in the application of herbal remedies that won her the trust and affection of many white settlers. It would seem that this affection was returned by Molly Ockett in the generosity she showed to these newcomers and in her habit of greeting them upon returning from her travels with a kiss, first on one ear and then on the other. Drawing by Danna Brown Nickerson |

|

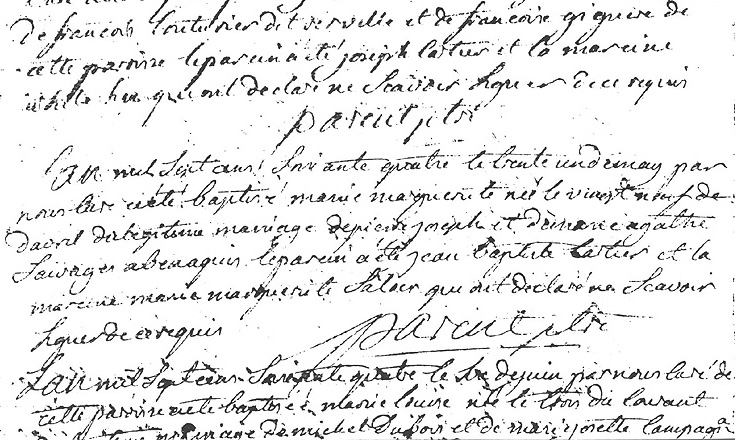

Wife

and Mother Molly Ockett's residence in Canada following Rogers' 1759 raid on Odanak may have been quite lengthy, as the baptism of her first living child, Marie Marguerite Joseph ("Molly Susup"), took place at the mission church at Odanak on May 31, 1764. The father of this child, Pierre Joseph ("Piol Susup") was apparently Molly Ockett's first husband, who died "some years before 1772." By 1766, Molly Ockett was in Fryeburg with a fellow Pigwacket named Jean Baptiste Sabattis. There is no record showing that Molly Ockett and Sabattis married, but they did have several children together, among whom were "Captain John Susup"; "Paseel" (Basil), who visited Bethel and was fairly well known to its early residents; a daughter who married a white man and lived near Derby, Vermont, in 1800; and a daughter who was the mother of Abbquasqua, a granddaughter of Molly Ockett who was twenty years old in 1789. Molly Ockett's relationship with Sabattis, though lasting several years, was a stormy one and ended when his former wife came to Fryeburg to lay claim to him. The challenge was resolved "in a very Indian way" by a fight between the two women. The match occurred on Fish Street in Fryeburg, witnessed by the wife of a local settler and Sabattis, who sat on a woodpile smoking his pipe. Reports vary on whether Molly Ockett won or lost, but weary of Sabattis's "intemperate habits and quarrelsome disposition," she soon left to join Captain Swassin's group of Indians who frequented the area between Lake Memphremagog and Umbagog Lake (the latter very near Bethel). Molly Ockett's daughter, Molly Susup, later lived with her mother in Bethel, attending school and playing with the white children. She seems to have caused her mother some parental concern when she had a child, Molly Peol, by an Indian much older than herself—a match her mother staunchly opposed. Molly Susup later married a Penobscot Indian "who quarreled with her and left her." History records that Molly Ockett was "very much modified" by her daughter's conduct and felt that her own character, as well as that of her daughter, was destroyed. Shown here is the 1764 baptismal record of Molly Ockett's daughter, Marie Marguerite. The original document resides in the Archives du Seminaire de Nicolet, near Québec City. Courtesy of Pat Stewart |

|

Moral

Character and

Religion Molly Ockett's religious faith and moral character were much admired by her white friends, and were often commented upon in their recollections. For example, Silvanus Poor of Andover wrote, "When she was traveling and felt in a pious mood, she always walked straight and if she came to a puddle of water in the road she wouldn't turn out for it." The concept of strait, as in "narrow" or "confining," and straight, as in "upright," emerges often in stories connected to Molly Ockett. She was obviously fond of the Biblical passage, "strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, that leadeth to life eternal; and few there be that find it." Although she retained her Catholic ties, journeying back to St. Francis on occasion to make confession to the priest, Molly Ockett regularly attended Protestant services when in the Bethel area, and referred to Methodists as those "drefful clever folks." She did not feel bound by white religious conventions, however, and occasionally spoke at Methodist meetings, a right normally reserved for male members of the congregation. A well known story about Molly Ockett and the Sabbath was recorded by Dr. Nathaniel T. True in 1863: She was easily

offended. She made her appearance one Monday morning with a

pailful of blueberries at the house of her friend, the wife of Rev.

Eliphaz Chapman of Bethel. Mrs. C. on emptying the pail found

them very fresh, and told her that she picked them on Sunday.

"Certainly," said Molly. "But you did wrong," was the

reproof. Mollyockett took offence and left abruptly, and did not

make her appearance for several weeks, when, one day she came into the

house at dinner time. Mrs. Chapman made arrangements for her at

the table, but she refused to eat. "Choke me," said she, "I was

right in picking the blueberries on Sunday, it was so pleasant, and I

was so happy that the Great Spirit had provided them for me." At

this answer, Mrs. Chapman felt more than half condemned for reproving

her as she did. Who could possibly judge this child of nature by

the same law that would condemn those more enlightened?

Another tale of Molly Ockett's church-going is connected with the town of Poland, Maine, where she was refused a seat at service. In a gesture that must have had a wonderful effect on the assembled congregation, Molly Ockett went outside, got a shingle bolt at a nearby mill and, carrying it inside the church, seated herself upon it directly in front of the pulpit, "where she attended every word during the service." Not surprisingly, Molly Ockett's religious reputation lingered with local residents long after her passing. The photo at left shows a carved portrayal of St. Mary as an Abenaki woman. This sculpture, which stands at the front of the Abenaki church at Odanak, Québec, serves as a reminder of Molly Ockett's strong religious beliefs. Courtesy of Pat Stewart |

|

Generosity Molly Ockett's generous nature is well documented by Henry Tufts, who met her in the 1770s. In his autobiography, published in 1807, Tufts records an instance of her generosity to a white man from Pigwacket (Fryeburg), who found himself without food for his family. The man journeyed to Bethel, as he "had used sometimes to visit the Indians for the benefit of hunting, trading, etc., by which means he had contracted some acquaintance with them and had heard that Molly Ockett always kept on hand a considerable quantity of money." Molly Ockett may have known the man from her recent residence in Fryeburg, as she loaned him twenty dollars, but "she rallied him on the score of his coming to borrow of the poor Indians, who (she said) were generally despised by the white people." She charged him to come the next winter and hunt furs to repay her, and this he did gladly, obtaining enough to repay her and have a surplus for his family. Another tale of Molly Ockett's generosity which came to a less fruitful end concerns the seed corn that she brought from Canada to Colonel McMillan of Conway, New Hampshire, to assist him in improving his crop. On her way to his house, she stopped to visit Squire Richard Eastman and family, leaving the bag of corn by some logs between the house and a nearby mill run by Noah Eastman. While she visited the Squire, someone came along and carried the precious seed into the mill where it was ground into flour. This incident gave rise to a new version of the old "Lucy Lockett" nursery rhyme (sung to the tune of Yankee Doodle): Molly Ockett lost her pocket / Lydia Fisher found it / Lydia carried it to the mill / And Uncle Noah ground it. Drawing by Danna Brown Nickerson |

|

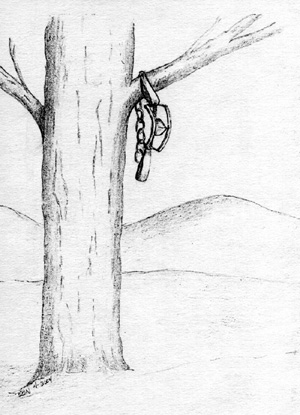

Storyteller Molly Ockett had a reputation, especially among the white settlers, as a talented storyteller. Because of her ability to relate stories of the past in great detail, her listeners became convinced that she was present during the events she described. For instance, Samuel Read Hall, an early resident of Rumford, Maine, believed Molly Ockett was born as early as 1685 based on her "recollection" of the Lovewell skirmish at Fryeburg in 1725. In truth, Molly Ockett was simply acting as an Indian "rememberer" or oral historian, transmitting past events she had heard from her elders and others around her. Molly Ockett also told her white friends other tales, some of which played into the settlers' superstitions and fears, and gained her a reputation as possessing destructive magical powers. She achieved this repute by punctuating her good works with occasional curses or warnings, some of which spawned legends that have been handed down through the generations. Three stories told by or about Molly Ockett, and featured in a booklet published by the Bethel Historical Society in 1991, are given below: She maintained that

when area Indians departed for Canada in 1755, at the start of the

French and Indian War, they buried a quantity of gold in Paris, marking

the spot by hanging two traps in a tree. This story took on added

zest when, in 1860, a length of chain was found enmeshed in a tree on

George Berry's farm in West Paris [near present-day "Trap Corner" on

Route 26]. The treasure did not come to light at that time, which

has allowed the legend to maintain its appeal for subsequent

generations, especially school children in the area.

Another "buried treasure" tale associated with Molly Ockett is traditional in East Bethel families. . . . Molly Ockett had buried some of her possessions in a cache on Hemlock Island in the Androscoggin River off East Bethel. A settler stole them and when Molly later recognized her hatchet in his cabin, she placed a curse on the family which is said to have had an adverse effect on their prosperity from then on. A variation of this story identifies the buried treasure as gold, but the Hemlock Island locale is the same. Stories told by Molly Ockett were not exclusively pleasant or historical, as she once predicted to people in West Poland [Maine] that the 18th of July would be so hot that water would boil in the wells and glass melt in the windows. This prophecy was told in a weird and vehement manner, disturbing those who heard it, and probably fostering the "witch" reputation Molly Ockett is reported to have had in Poland. Drawing by Danna Brown Nickerson |

|

Sociability One of Molly Ockett's outstanding traits was her ability to move easily in and out of the white communities. In her lifetime, she saw her native world devastated—her people killed, their land taken, and their resources depleted or destroyed—and yet she repeatedly showed kindness and sympathy toward individuals descended from the very people who had carried out these acts, making one wonder if she didn't carry a deeply-rooted, but suppressed, resentment against white folk in general. In any event, stories of gloom and doom seem relatively rare in connection with her life. More typical are recollections of her friendship with the settlers with whom she maintained close contact while on her travels. She often took her meals with them and repeatedly demonstrated a particular fondness for rum. Dr. Nathaniel T. True, writing in 1863, told of one occasion when Molly Ockett visited the Dr. Moses Mason House, now owned by the Bethel Historical Society: When provided with a

glass in any of the families which she visited, she would become very

loquacious and entertain her company with stories and amusing

anecdotes. . . . Her shrewdness was well shown on a visit at the Hon.

Moses Mason's in Bethel. She asked for some rum. The Doctor

knowing her weakness in this respect, poured out a half glass, being an

allowance much smaller than usual, and told her this was all he had for

her. "J-e-s-t enough," was her quick reply, as she devined the

Doctor's motive.

Painting by Danna Brown Nickerson |

|

Craftswoman Molly Ockett was extremely adept in traditional Abenaki crafts, a fact much admired by the early white settlers of this region. Using techniques passed down through generations of her family, she created baskets, moccasins, leather-work, bark boxes, and pottery. She was especially skilled in beadwork, quillwork, weaving, and embroidery, as confirmed by a handful of surviving examples of her talents. A small birchbark box with cover, decorated with dyed porcupine quills (photo, left), was made by Molly Ockett for the family of Israel Kimball (1769-1829) of Middle Intervale (Bethel) and is now in the collection of the Bethel Historical Society; a larger box of similar design was given to the Maine Historical Society in 1860 by Mrs. John Kimball of Bethel. A pudding dish made by Molly Ockett for Mrs. Bragg of Andover was described as "a work of art [that was] white with a roll on top, resembling the finest whiteware." A duck feather bed made by Molly Ockett for Mrs. Swan of Bethel attests to her skill as a hunter and craftswoman. The Maine Historical Society also possesses a decorated folding pocketbook originally made for Eli Twitchell of Bethel. The hemp material for this purse (currently on display in the Maine State Museum's "12,000 Years in Maine" exhibit), which is covered with Indian-style embroidery using the long white hairs of a moose dyed red, green, blue and yellow, was prepared by Molly Ockett, though the actual purse, featuring a silver clasp dated 1778, was not constructed by her. |

|

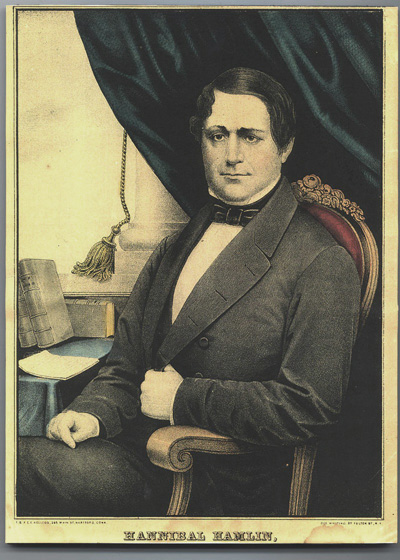

Indian

"Doctress" Molly Ockett's intimate understanding of the natural environment and her use of herbal remedies to cure many of the afflictions of both Indians and white settlers earned her the respect and gratitude of those around her. Henry Tufts called her "the great Indian doctress" and devised ways of getting Molly Ockett to reveal her secrets, a favor normally reserved only for those who were especially kind to her. But the question remains—why did the white settlers trust Molly Ockett to treat them during times of illness or accident? A decided lack of health-care options (Bethel's first physician, Dr. Timothy Carter, did not set up practice until 1799), a traditional reliance in rural New England on midwives for general medical care (in addition to delivering babies), and a lack of knowledge concerning local herbal remedies all worked to her advantage. By successfully turning raw materials (including Bloodroot, illustrated here) into tonics, salves, or poultices, Molly Ockett gained status in the world of the white settlers. Molly Ockett often came to Newry and Riley Plantation ("Ketchum"), where she taught Martha Russell Fifield to count in Indian, and shared with her some medicinal knowledge and instructions for making root beer and dyes. As a midwife, Molly Ockett attended the birth of Andover's first white child, born to her friend Sarah Merrill in July 1790. The Poland Spring mineral waters, world famous by the late 19th century, were said to have been esteemed by Molly Ockett, who was regarded by some of Poland's early residents as a witch, though skillful as a doctor. Perhaps the most re-told story of Molly Ockett's healing powers is her cure during the winter of 1809-10 of the infant Hannibal Hamlin, who later became Abraham Lincoln's first vice-president. |

| Molly Ockett Meets

Henry Tufts One of the earliest and most detailed accounts of Molly Ockett's life comes from a book about Henry Tufts (1748-1831), a shady character who lived among the Abenaki of western Maine between the spring of 1772 and the spring of 1775, a three-year period during which he learned the Indian language, their medical practices, and their customs. In and out of jail during much of his life, Tufts was, at various times, a counterfeiter, an army deserter, a thief, a bigamist, a doctor, and a preacher. His main reason for visiting the Indians was to find a cure for a serious knife wound he had received in an accident, and fortunate he was that Molly Ockett was there and willing to administer aid. First published in 1807 as A Narrative of the Life, Adventures, Travels, and Sufferings of Henry Tufts, this account provides a rare and intimate glimpse into the private world of an Indian healer during the late 18th century. A new edition of Tufts' book, re-titled The Autobiography of a Criminal, was issued in 1930, and several excerpts from that volume appear below. Tufts died at Limington, Maine, in 1831, "in the eighty-third year of an uncommonly misspent life."  After many and

repeated efforts, I reached the Pigwacket country [Fryeburg, Maine,

vicinity], where I suspended my travels a few days, to recruit, in some

degree, my exhausted strength and spirits. . . . But now I was

frequently put to my trumps to trace the most direct course toward the

Indian encampments, which, as yet, were thirty miles distant. . . . No

long time supervened, ere ascending a great hill, I had a view, for the

first time, of their camps and wigwams in Sudbury Canada [Bethel]. . . . After many and

repeated efforts, I reached the Pigwacket country [Fryeburg, Maine,

vicinity], where I suspended my travels a few days, to recruit, in some

degree, my exhausted strength and spirits. . . . But now I was

frequently put to my trumps to trace the most direct course toward the

Indian encampments, which, as yet, were thirty miles distant. . . . No

long time supervened, ere ascending a great hill, I had a view, for the

first time, of their camps and wigwams in Sudbury Canada [Bethel]. . . .On my approach, their chief, whose name was Swanson, gave me a very cordial reception, and presently ordered his domestics to prepare dinner. . . . I acquainted him with my circumstances, and the design I had formed of residing in [Sudbury] Canada for a season. He seemed pleased with my intentions, and gave me free toleration to abide in his tribe during pleasure. To these instances of benignity he superadded another, which was to enjoin Molly Occut, at that time the great Indian doctress, to superintend the recovery of my health. . . . . . . I made direct application to the lady for such medicines as might be suitable to my complaints. She was alert in her devoirs, and supplied me for present consumption, with a large variety of roots, herbs, barks and other materials. I did not much like even the looks of them; for to have contemplated an encounter with the formidable forage might have staggered the resolution, doubtless, of a much greater hero than myself. However, I took the budget with particular directions for the use of each ingredient. My kind doctress visited me daily, bringing new medicinal supplies, but my palate was far from being gratified with some of her doses, in fact they but ill accorded with the gust of an Englishman. Nevertheless having much faith in the skill of my physician, I continued to swallow with becoming submission, every potion she prescribed. Her means had a timely and beneficial effect, since, from the use of them, I gathered strength so rapidly, that in two months, I could visit about with comfort. The Autobiography of a Criminal; Chapter VII, Life with the Indians, pp. 59-64 Returning health inspired my breast with new-born hope, and was a source of lasting consolation. And now curiosity prompting me to visit the Indian settlements in this department . . . I followed the daily practice of traveling from place to place, until I had visited the whole encampment, and . . . found there might be about three hundred inhabitants in this quarter. The entire tribe, of which these people made a part, was in number about seven hundred of both sexes, and extended their settlements, in a scattering, desultory manner, from lake Memphremagog to lake Umbagog, covering an extent of some eighty miles. . . . I continued the salutary exercise . . . until my health was restored in as full and perfect a manner, as I had possessed that blessing at any former period. This happy restoration to pristine ability I attributed principally to the good offices of my doctoress, who during my convalescence, was indefatigable in her care and attention. Her character was, indeed, that of a kind and charitable woman. . . . Since beginning to amend in health under the auspices of madam Molly, I had formed a design of studying the Indian practice of physic, though my intention had hitherto remained a profound secret. Indeed I had paid strict attention to everything of a medical nature [and] frequently was I inquisitive with Molly Occut, old Philips, Sabattus and other professed doctors to learn the names and virtues of their medicines. In general they were explicit in communication, still I thought them in possession of secrets they cared not to reveal. . . . As divers English people used occasionally to visit us to purchase furs and the like, I disposed of my share to those visitants; and among other articles procured ten gallons of rum, with which I regaled a number of my Indian friends, as long as it lasted. By this exploit I so far engaged their good will and gratitude, that no sooner did I acquaint them with my desire to learn the healing art, than they promised me every instruction in their power. . . . The Autobiography of a Criminal; Chapter VII, Life with the Indians, pp. 64-68 It had long been an approved custom, among the savages of Sudbury [Canada], to visit Québec, every spring of the year. . . . The principal motives of such journeys were the purchase of absolution of sin, and to have the souls of deceased friends prayed out of purgatory. . . . About the beginning of May, this year, a considerable party, laden with furs, as customary, set out for Québec, but now Molly Occut herself made one of the itinerants. Her motives, in undertaking so troublesome an expedition, were the pardon of her own sins, and the strong desire she had that the soul of her deceased husband should be prayed out of purgatory. He had been dead several years, and she had hitherto neglected to discharge this pious duty. Resolving to atone now for former remissness, she set out . . . with the rest of the company, and with a valuable pack of furs at her back. After the absence of two weeks they returned, bringing home divers articles, which they had in exchange for their furs. On arrival, several of the adventurers recounted . . . a pretty ludicrous anecdote of the worthy doctoress. It related to a transaction that took place between her and a certain Catholic priest, at the time of his praying her husband out of purgatory. . . . Molly having disposed of her furs for cash, about forty dollars . . . went directly to a priest, and acquainted him with her wishes, requesting to know the sum he should ask for performing the godly services. The crafty priest, knowing the sum she had recently received, demanded the whole forty dollars, and insisted on the money being told down, previous to his entrance on the sacred duties. With this unreasonable request she complied . . . and then the treacherous old Levite, with much pretended sanctity, began the solemn farce. In the first instance he gave her pardon and absolution, and next undertook to petition for the departed soul of her late husband. At length . . . he informed her that the business was happily completed, and that her husband's soul was safely delivered from the bonds of purgatory. She, however, was very particular in her inquiries, whether he were certainly clear or not. The old priest asseverated repeatedly that he was absolutely free. On this she scraped the money off the table into the corner of her blanket, and tying it up was about to depart. The priest some nettled, demanded the meaning of her maneuver, and threatened to remand her husband back to purgatory, unless she gave him the money. Her reply was that she knew her husband too well to believe it in a priest's power to do that, for (added she) my husband was always a very prudent man. I have often observed, when we used to traverse the woods together, if he chanced to fall into a bad place, he always stuck up a stake, that he might never be caught there any more. Without further ado, she made the best of her way off, leaving the poor ecclesiastic to console himself for the loss of the money in the best manner he could. . . . When Molly had returned from Québec . . . I renewed my intense application to medicinal inquiries; generally attending my patroness, when she visited her patients, gaining, by those means, a much better insight into the Indian methods of cure than had otherwise been possible. The Autobiography of a Criminal; Chapter VIII, The Daughter of King Tumkin, pp. 78-81 |

|

| Molly Ockett and the Last Indian Raid Perhaps the most thrilling event to occur in the Bethel region during the American Revolution was the "Last Indian Raid in New England," which took place in the upper Androscoggin River valley on August 2 and 3, 1781. Led by "king" Tumkin Hagen, who had long resented white settlement in the area, a small band of Indians "painted and armed with guns, tomahawks and scalping knives" plundered several houses in Newry, Bethel, and Gilead, Maine, capturing three men and killing a fourth in the latter township. Crossing into New Hampshire, the attackers then raided several cabins in Shelburne, seizing an African-American man named Plato and killing Peter Poor, an early settler. The Indians, with their captives, soon departed for Canada, leaving the remaining inhabitants of Shelburne to spend a restless night atop a local prominence still known as "Hark Hill." Soon thereafter, a militia of thirty Fryeburg men, led by Molly Ockett's ex-partner Sabattis, made a futile attempt to pursue Tumkin Hagen's group and rescue the prisoners. Among the latter was Lt. Nathaniel Segar of Bethel, whose "captivity narrative" published in 1825 highlights the tentative nature of Anglo-Indian relations previous to the 1783 Treaty of Paris that officially ended the Revolutionary War. Molly Ockett's connection with the 1781 Raid involves an incident that occurred either before or just after the main skirmish. When she learned of Tumkin Hagen's plan, she rushed several miles through the woods to the camp of Colonel Clark of Boston to tell him that he, too, was to be killed. This magnanimous act, which again demonstrates Molly Ockett's aversion to violence between her fellow natives and their white neighbors, is recounted in Benjamin G. Willey's Incidents in White Mountain History, published in 1856: During the last years

of the American Revolution, the northern Indians seem to have

determined to make a final struggle for their hunting-grounds and home.

. . . No general battle was fought, but after committing many murders

and barbarities on the settlers, and greatly annoying them, they

retired, forgetting their revenge in the sad and weak condition of

their tribe. One Tom Hegan . . . was particularly active in

waylaying and killing the whites. He figures conspicuously in all

the cruel Indian stories of this region. Sometimes in the employ

of the British, and sometimes impelled onward by his own deep hatred,

he was very bold, and bloody, and barbarous, and for a long time a

terror to the settlers.

A Col. Clark, of Boston, had been in the habit of visiting annually the White Mountains, and trading for furs. He had thus become acquainted with all the settlers and many of the Indians. He was much esteemed for his honesty, and his visits were looked forward to with much interest. Tom Hegan had formed the design of killing him, and, contrary to his usual shrewdness, had disclosed his plans to some of his companions. One of them, in a drunken spree, told the secret to Molly Ockett, a squaw who had been converted to Christianity, and was much loved and respected by the whites. She determined to save Clark's life. To do it, she must traverse a wilderness of many miles to his camp. But nothing daunted the courageous and faithful woman. Setting out early in the evening of the intended massacre, she reached Clark's camp just in season for him to escape. Tom Hegan had already killed two of Clark's companions, encamped a mile or two from him. He made good his escape, with his noble preserver, to the settlements. Col. Clark's gratitude knew no bounds. In every way he sought to reward the kind squaw for the noble act she had performed. For a long time she resisted all his attempts to repay her, until at last, overcome by his earnest entreaties and the difficulty of sustaining herself in her old age, she became an inmate of his family, in Boston. For a year she bore, with a martyr's endurance, the restraints of civilized life; but at length she could do it no longer. She must die, she said, in the great forest, amid the trees, the companions of her youth. Devotedly pious, she sighed for the woods, where, under the clear blue sky, she might pray to God as she had when first converted. Clark saw her distress, and built her a wigwam on the Falls of the Pennacook [Rumford Falls], and there supported her [and] often did he visit her, bringing the necessary provision for her sustenance. |

|

|

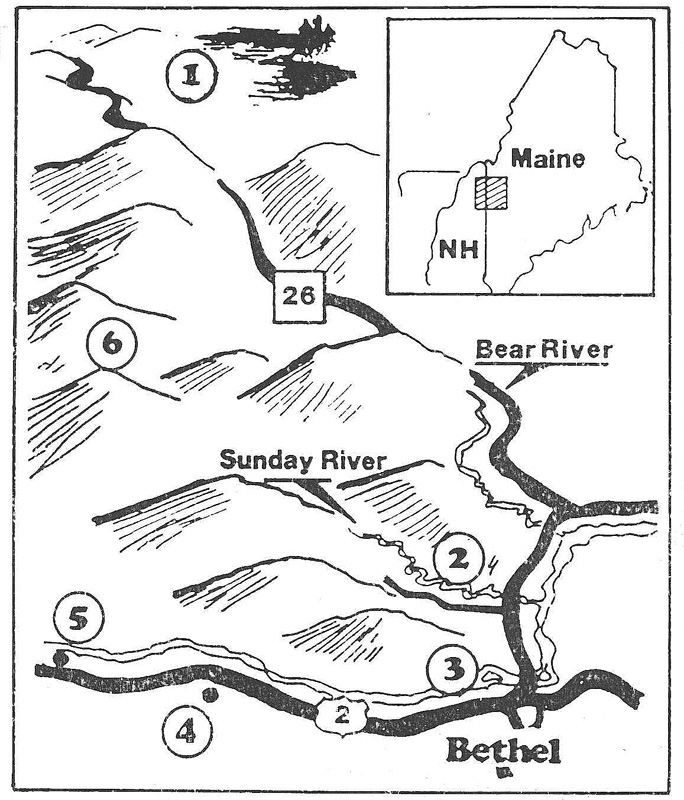

This map pinpoints

sites connected with New England's Last Indian Raid of August 2-3,

1781: (1) Indians venture south from Umbagog Lake; (2) Barker homestead

on Sunday River attacked; (3) Captives taken at Clark house in Bethel;

(4) Gilead settler killed and scalped; (5) Shelburne settler killed and

another captured; (6) Indians and captives flee over Mahoosuc Mountains

to Canada. Tumkin Hagen, leader of the raiding party, also

intended to kill Colonel Clark, camped in the vicinity, but Molly

Ockett warned the Boston man in time to save his life. Map by Donald Gilman Bennett |

|

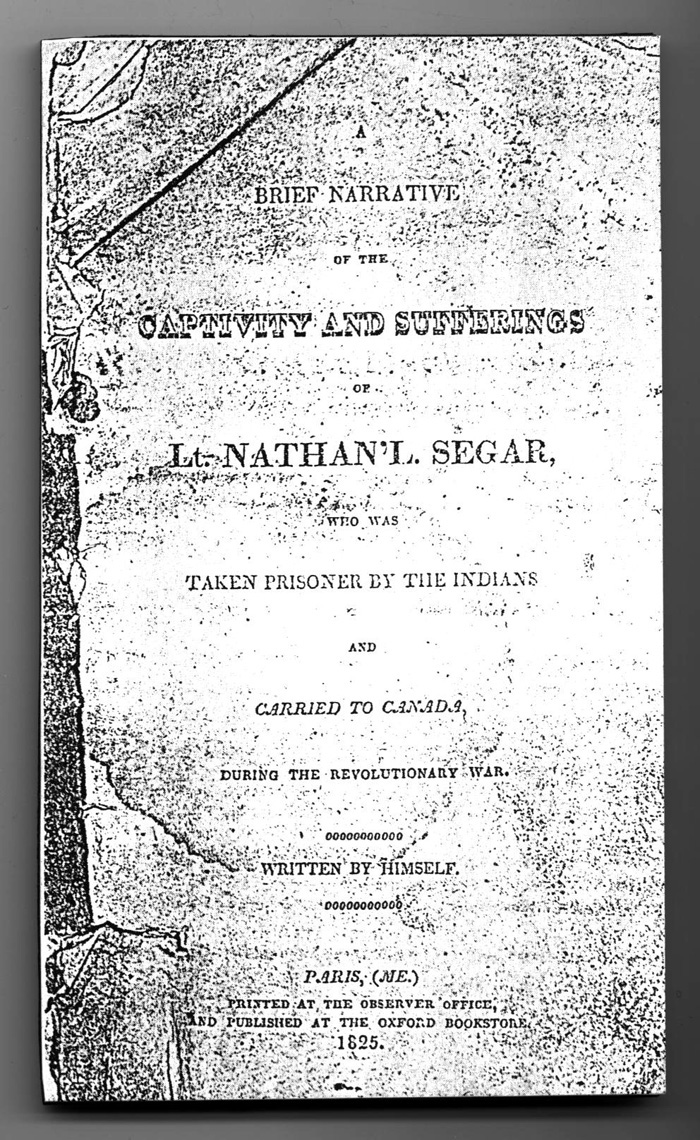

One of the most

interesting documents relating to Anglo-Indian relations during the

Revolutionary War is the "captivity narrative" of the early Bethel

settler Nathaniel Segar, published in 1825. It was at the time of

the Last Indian Raid in New England that Molly Ockett saved the life of

Colonel Clark of Boston. |

|

In August 1931,

the people of Bethel celebrated the 150th anniversary of New England's

Last Indian Raid with a parade, speeches, a special edition of the

local paper, and a "pageant" meant to recreate that long-ago

skirmish. The grand climax of this spectacle was the burning of a

settlers cabin—a highly dramatic event that did not take place during

the actual 1781

Raid. |

|

Around 1800-1805,

Molly Ockett resided for a year in Boston with the family of Colonel

Clark, whose life she had saved in 1781. Though she probably had

visited the city in her youth, Molly Ockett yearned for the North

Country and was thankful to return to her familiar haunts in the

Androscoggin valley. Courtesy

of Pat Stewart |

|

Grateful to Molly

Ockett for saving his life and aware of her unhappiness living in

Boston, Colonel Clark built her a wigwam near the "Great Falls" at

Rumford, some twenty miles downriver from Bethel. This tremendous

cataract, shown here in a late 19th century photo originally

published in William B. Lapham's History

of Rumford, Oxford County, Maine (1890), may have had symbolic

meaning to Molly Ockett and others in her kin-group, who regarded

themselves as "original proprietors" of the lands upriver of the Great

Falls. |

| Treasure Legends Rumors of buried Indian treasure have long been common in western Maine and northern New Hampshire since the early days of white settlement, with many of the stories centering on Molly Ockett. The truth of these stories is lost to time, but it is known that Molly Ockett and her kin-group did accumulate money and jewelry through the sale of furs, for medical services, and in trade. It is also likely that their nomadic life-style led them to cache possessions in secret spots, knowing that they could collect them upon their return. Versions of two of the most frequently told stories concerning Molly Ockett's buried treasure are presented here. In the Shadow of White Cap The following Molly Ockett "treasure legend" was recorded by Silvanus Poor of Andover, Maine, in a January 12, 1861, letter to Dr. Nathaniel T. True of Bethel. Dr. True later quoted the entire letter in his article "The Last of the Pequakets: Mollocket," published in the Oxford Democrat in 1863. Tradition says

that she formerly had quite a sum of money and that it was buried in a

tea kettle on a small hill in the vicinity of White Cap [a high,

granite-topped mountain in the northern part of Rumford], now called

Farmer's Hill in this town, by the side of a large stone with a cross

on it, and that there were guides to the large stone on smaller ones

from a certain point in the Ellis River in the shape of an Indian

arrow with barb and quiver. Much time was spent looking for it,

but

the trouble was to find the starting point. Several years ago, a

Mr.

F— discovered the picture of an Indian's arrow on a stone in the

woods. He stated the fact to an old gentleman who remembered the

tradition. Search was immediately made, and the large stone

marked

with a cross was found. On digging about it they discovered that

excavations had been made there before. It was Saturday and night

came

on before the money was found, and the secret leaked out. The

party

who had made the discovery went on Monday morning and reached the spot

just in season to see two men depart with something like a kettle

hanging upon a pole, and borne on their shoulders, who had been digging

on the Sabbath and found the prize.

A Story of Hemlock

Island

During

the

last

years of the 19th century, Bethel native Peter Smith Bean (1824-1911)

wrote a series of recollections that were published in the Oxford

County Advertiser of Norway, Maine, under the title "Upton, B,

in the

Twenties." Excerpts from the December 11, 1891, article in that

series, entitled "Molly Lockett's Buried Treasure on Hemlock Island,

Bethel, Maine," follow.There is a tradition

that a kettle of money was buried on Hemlock Island in the Androscoggin

River in Bethel. It belonged to the tribe that Molly Lockett

belonged to. . . . They put all of their money into an iron pot and

buried it on the upper end of Hemlock Island. They selected a

place where two hemlock trees grew near each other, the roots running

past each tree and interlocking, leaving a space between the trees free

from the roots. After carefully placing birch bark in the pot for

lining, they put in the jewelry and money . . . The money was French

and British gold. The silver was mostly Spanish coins . . .

Tradition says that there was over a thousand dollars besides a large

amount of valuable jewelry. . . .

Molly Lockett's story about the money: She says she was so young that she forgot about the burying of the pot of money; that the party who buried it . . . were soon engaged in war with another tribe . . . Those that escaped were attacked with diseases and kept dying until Molly's parents were all there was left of the original party. Molly's father was taken down with the small pox and died. . . . Before [the mother] died, she made Molly promise to return to the place of the buried treasure and dig it up. . . . In due time Molly arrived at the island [and] began to search for the twin hemlocks, but none were to be found. Everything had changed during the many years that had passed since she left the island in her youthful days. . . . For years Molly made the island her headquarters, there being plenty of fish in all the streams in that vicinity. She was living there when grandfather Daniel Bean came to Bethel in 1782, so he said. . . . After a while the settlers noticed that Molly did a large amount of digging on the upper end of the island. When they questioned her . . . she said she was digging for roots to make medicine of. After a while she did not dig so much, but seemed to be in a deep study by spells and kind of down hearted. One fall she came here. She was sick when she came [and] thought she would never recover. She called grandfather [Ithiel Smith, Jr.] to her bedside and said "Ithiel, I want to tell you something but you must keep it to yourself if I live, but if I die you can do as you please in the matter." After grandfather promised to do as she told him, Molly told him the story of the buried treasure on Hemlock Island . . . Molly got well again [and] told grandfather he might have one-half of it if he could find the pot. Grandfather spent some time digging . . . but never found it. The last time I was at grandfather's in the year of 1835, [he] told me about the treasure . . . Molly Lockett had been dead for years and sleeping in her grave at Andover. . . . Time passed on until 1844. I had come into possession of an instrument that gold or silver would attract it so strong that a person might hide a fifty cent piece outside of the house . . . and I could find it in a few minutes. I started for Maine determined to explore Hemlock Island for all it was worth. But I was too late [and] the treasure had been taken away by another person. That other person was born and raised in Newry but drifted as far as Cincinnati, Ohio. He found it by aid of the same kind of instrument as I had . . . This person who is supposed to have found the Hemlock Island pot of treasure was Prof. John Locke. A short time after, a man by the name of Eames went to the island out of curiosity and discovered there where someone had dug up the pot of treasure. . . . The ground had been dug over many times where it was buried, but no one went deep enough to find it. During the lapse of years, the floods had left deposits of soil on the island yearly which had added greatly to the depth of earth above the treasure. That is the reason that Molly Lockett could not find it. |

|

| The

Lonesome Trail "After the close of the Revolutionary War . . . the old soldiers began to look eastward as a sort of promised land; large numbers came, and Sudbury Canada [Bethel] had its full quota." These remarks by one of Bethel's 19th century historians describe the beginnings of an era of general expansion in northern New England, and one which saw Maine's white population soar from 56,000 in 1783 to 300,000 in 1820—an increase of 450 percent. In the four decades between the time of the Last Indian Raid (1781) and Maine statehood (1820), many settlements in this region not only incorporated themselves as "towns," but also made significant strides in the areas of transportation, industry, education, religion, and local government. The development of compact villages, the establishment of post offices (Bethel's first post office opened at the Society's Mason House in 1815), and the proliferation of farms along the Androscoggin and other major waterways in the region gave visible testimony to this dramatic transformation. Surrounded by growing numbers of white settlers, some of whom earned part of their living by stripping the forests of their trees, many of the Abenaki remaining here after the Revolution surrendered their long and tenacious hold on their ancestral lands and departed for Canada or more remote parts of northern Maine and New Hampshire. For those few—including Molly Ockett—who remained, the dusty and wagon-clogged roads crisscrossing this territory were lonesome trails indeed. |

|

|

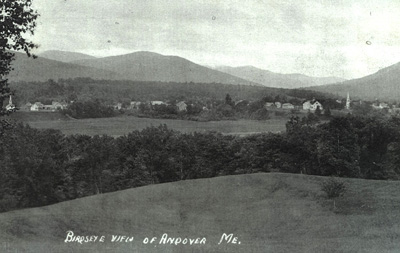

According to an 1861

letter written by Silvanus Poor of Andover, Maine, to Dr. Nathaniel T.

True of Bethel, Molly Ockett was living at the forks of the Ellis River

in Andover with "old Phillip's (an Indian) family," when Ezekiel

Merrill, that town's first settler, moved there with his family in May

of 1789. According to Poor, "She was probably about 60 years at

that

time [and] was now too old for the chase, but spent much of her time

about the lakes and ponds in this vicinity. She also used to

bring in and dry moose meat that was killed by the other Indians in the

spring of the year. . . . She spent about half of her time here when

she was not trapping, and the remainder in Bethel and vicinity, making

baskets, moccasins, wampam [sic], &c. She was industrious and

peaceable, and was formerly quite handsome . . . and had a large supply

of bracelets, jewelry, &c., but most of it was given away or

disposed of before her death." |

|

In July of 1790,

Molly Ockett served as midwife at the delivery of Susan Merrill, the

first white child born in Andover, Maine. The child's parents,

Ezekiel and Sarah Merrill, settled in Andover in 1789 and constructed a

small log shelter on the site of this massive

Colonial Revival house, which still stands in 2007 and may contain

elements

from a dwelling built by the Merrills in 1791. Andover's first

white family, the Merrills maintained frequent and close ties with the

local Abenaki, including Molly Ockett. One local history mentions

that "in the large hall of the new house, Indians were often permitted

to lie stretched along the floor, wrapped in blankets, with their heads

toward the brick fireplace." |

| A

"Curious" Introduction: Vermont, 1799-1800 The following information from Samuel Sumner's 1860 History of Missisco Valley (Vermont) documents a time in Molly Ockett's life when she and other Abenaki were struggling to survive in the northern reaches of Vermont. Several families

moved into Troy and Potton in 1799, and in the winter of 1799 and 1800,

a small party of Indians, of whom the chief man was Capt. Susup, joined

the colonists, built their camps on the river, and wintered near

them. These Indians were represented as being in a starving

condition, which probably arose from the moose and deer being destroyed

by the settlers. Their principal employment was making baskets,

birch bark cups and pails, and other Indian trinkets. They left

in the spring and never returned. They appeared to be the most

numerous party and resided the longest time of any Indians who ever

visited the valley since the commencement of the settlement.

One of these Indians, a woman named Molly Orcutt, exercised her skill in a more dignified profession, and her introduction to the whites was rather curious. Molly Orcutt was known as an Indian doctress, and then resided some miles off, over the Lake. She was sent for [to examine a white man's hand that was severely bruised in a "drunken frolic"], and came and built her camp near by, and undertook the case, and the hand was restored. Her medicine was an application of warm milk punch. Molly's fame as a doctress was not raised. The dysentery broke out that winter violently among children, and Molly's services were again solicited, and she again undertook the work of mercy, and again she succeeded. But in this case Molly maintained all the reserve and taciturnity of her race [and] retained the nature of her prescription to herself. She prepared the nostrum in her own camp, and brought it in a coffee pot to her patients, and refused to divulge the ingredients of her prescription to anyone; but chance and gratitude drove it from her. In the March following, as Mr. Josiah Elkins and wife were returning from Peacham, they met Molly at Arnold's Mills in Derby; she was on her way across the wilderness to the Connecticut River, where she had a daughter married to a white man. Mr. Elkins inquired into her means prosecuting so long a journey through the forests and snows of winter, and found she was scantily supplied with provisions, having nothing but a little bread. With his wonted generosity, Mr. Elkins immediately cut a slice of pork of 5 or 6 pounds weight out of the barrel he was carrying home and gave it to her. My informant remarks she never saw a more grateful creature than Molly was on receiving this gift. "Now you have been so good to me," she exclaimed, "I will tell you how I cured the folks this winter of the dysentery," and told her receipt. It was nothing more or less than a decoction of the inner bark of the spruce. |

|

|

Molly

Ockett Saves Hannibal Hamlin The most famous story connected with Molly Ockett's healing powers has to do with her cure of the infant Hannibal Hamlin, who was born at Paris Hill, Maine, on August 27, 1809, and who later became Lincoln's first vice-president. During the winter of 1809-10, Molly Ockett was traveling through the town of Paris, some twenty miles south of Bethel, when, in foul weather, she sought shelter with the white residents at Snow's Falls. According to oral tradition, she was turned away, whereupon she uttered a curse on the place, said to be responsible for the lack of success of subsequent business enterprises in that neighborhood. Molly Ockett struggled along to the village of Paris Hill, where she was welcomed into the home of Dr. Cyrus Hamlin and his wife, Anna Livermore Hamlin. Returning later that spring, she found Mrs. Hamlin "sitting in her doorway one day, rocking her feeble infant." Molly Ockett "looked at the child very intently . . . and then said with great earnestness, 'You give papoose milk warm from cow, or he die.'" The infant, Hannibal Hamlin, "thrived with great rapidity" in response to this treatment, and Molly Ockett was thus able to repay the Hamlins for their earlier kindness. |

|

During the last few

years of her life, Molly Ockett was an occasional visitor to the Bethel

home of Dr. Moses Mason and his wife, Agnes M. Straw. Their

Federal style house, begun in 1813, is shown here in a circa 1905

photograph. The Mason House is now a museum facility operated by

the Bethel Historical Society. |

|

Map of Molly Ockett's

range within the Abenaki homeland. Traveling on foot or by canoe,

Molly Ockett journeyed far and wide throughout much of northern New

England and southern Québec during her lifetime. Courtesy of Pat Stewart |

| The

Last of the Pigwackets Molly Ockett was residing with the Abenaki chief Metallak and his kin-group near Upper Richardson Lake, north of Andover, Maine, early in 1816 when she became ill, no doubt as a result of increasing age and an active life of hard work and migratory travel—much of the latter done on foot. The following account of Molly Ockett's last days is based on the reminiscences of Silvanus Poor of Andover and was recorded by his niece, Agnes Blake Poor, in her 1883 manuscript "Andover Memorials," since published in book form. In the spring of

1816, Mollockett being at the [Richardson] lakes, was taken ill at

Beaver Brook, above the narrows on Lake Molechunkamunk. She was

assisted down to Andover by some friendly Indians, who remained there

about two weeks taking care of her. At the end of that time they

represented to the authorities of the town that it would be better for

the town to take charge of her, than to have the whole party on their

hands, for if they stayed to take care of her they could not hunt and

support themselves. They then left, and the town authorities took

charge of her. They made a contract with Mr. Thomas Bragg to keep

her the rest of her life. She so strongly objected to enter[ing]

his

house, saying, "Me want to die in a camp, that is the home for poor

Indian," that a small camp was built for her, in which she remained

till her death, receiving every attention necessary for her

comfort. She was very patient in her last illness, and when asked

if she were prepared to die, replied, "Me guess so, be here good many

years." She died August 2, 1816, and was buried in the Andover

graveyard. A funeral sermon was preached for her by the Rev. John

Strickland, which was largely attended. A stone was erected to

her memory, from the proceeds of a celebration held in Andover on the

Fourth of July, 18[67] for that purpose. After her death, her

effects, which were scattered about, some in Andover, some in Newry,

etc., were collected and sold at public auction, and the proceeds were

nearly sufficient to cover the expenses of her illness and

burial. Some of these articles are still in existence, and I

possessed at one time the pouch in which she was accustomed to carry

her jewelry.

|

|

|

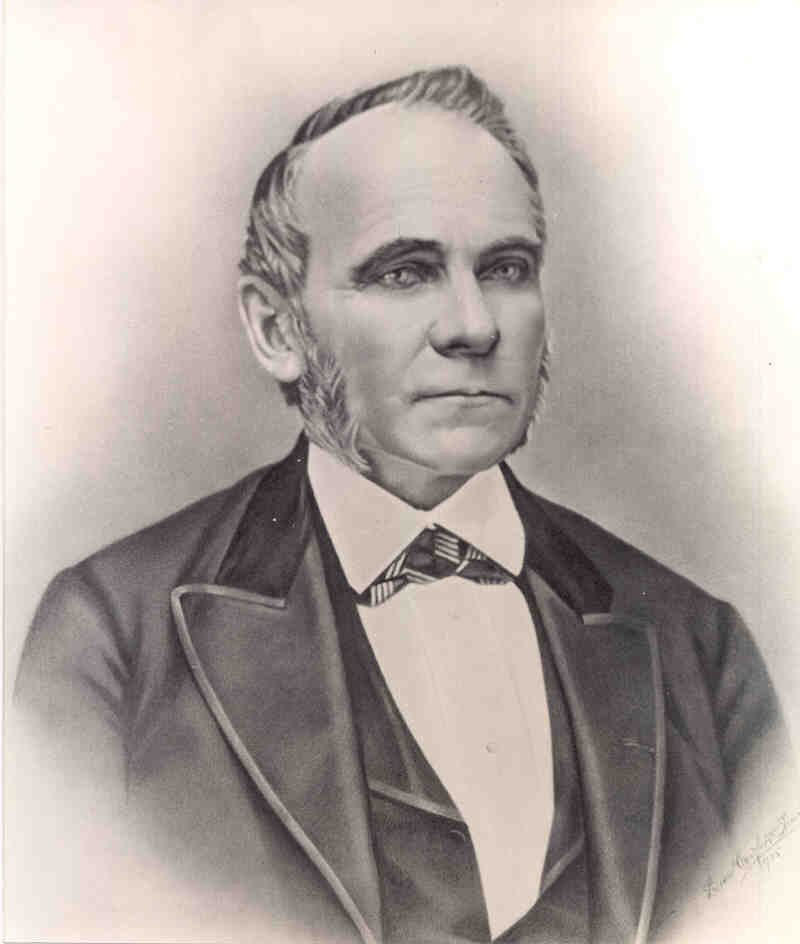

For many years

headmaster at Gould Academy in Bethel, Dr. Nathaniel T. True

(1812-1887) was an antiquarian, newspaper editor, and amateur scientist

keenly interested in the language and customs of the Abenaki. Dr.

True contributed numerous articles on Indian-related topics to popular

and scholarly journals and newspapers of his day, including "The Last

of the Pequakets: Mollocket," written for the Maine Historical Society

and published in the January 2, 1863 issue of the Oxford Democrat. This

account, widely regarded as one of the most reliable sources about

Molly Ockett's life, was based on interviews with, and correspondence

from, people who actually knew her. |

|

In 1867, the women of

the Congregational Church at Andover, Maine, raised money to erect a

gravestone over Molly Ockett's last resting place in that town's

Woodlawn Cemetery. Inscribed to the memory of the "last of the

Pequakets," the marble tablet was officially dedicated during Andover's

Fourth of July festivities. Bethel's Dr. Nathaniel T. True, who

had long studied Maine's Indians, gave the oration and set the stone in

place with the assistance of a man who had helped dig Molly Ockett's

grave some fifty years earlier. Courtesy

of Pat Stewart |

| An

Enduring Legacy For nearly two centuries—since her death in 1816—the story of Molly Ockett and her world has captured the interest of historians, writers, and generations of local residents. These "stories" have been re-told, expanded upon, and fictionalized, but, for many people, an underlying interest in the real Molly Ockett fortunately endures. The distance between "Princess Molly Ockett" of Bethel's annual summer festival and Mareagit—the determined original proprietor, the "Indian doctress," the "pretty and genteel squaw," and the friend of the white settlers—is certainly great. Yet Molly Ockett's important qualities of ability and personality transcend the many years that have passed since her birth. Her generosity, accomplishment, self-reliance, and determination to walk a straight path in difficult and confusing times are qualities as worthy of admiration in the twenty-first century community of "Princess Molly Ockett" as they were in the world of the original Molly Ockett, and constitute a unique and lasting legacy. |

|

|

Among the many

geographic locations in this region associated with Molly Ockett that

can be visited today is "Molly Ockett's Cave" in Fryeburg.

Located at the base of a rocky outcrop known as Jockey Cap, this stone

shelter is situated a short distance from the site of the Indian

village of Pigwacket, where Molly Ockett spent much of her youth.

Molls Rock, on the eastern shore of Umbagog Lake, and Moll Ockett

Mountain, in the nearby town of Woodstock, also preserve her

name. Courtesy of Pat Stewart |

|

A modern consequence

of Molly Ockett's longstanding fame has been the use of her name in

connection with several area businesses, institutions, and

events. Other Abenaki of Molly Ockett's time, including Metallak

and Sabattis, have had their names "preserved" in a similar manner. |

|

"Molly Ockett and Her

World" was originally displayed at the Bethel Historical Society from

July 17,

2004, through May 31, 2007. The Bethel Historical

Society extends its appreciation to the following individuals for their

assistance in making the exhibit possible: Catherine S-C.

Newell; Patricia Stewart; Pauline T. Bartow; and Bunny McBride.

Funding

for the exhibit was provided by the Maine State Organization Daughters

of the American Revolution and the Molly Ockett Chapter

Daughters of

the American Revolution, Fryeburg, Maine.

|

|

Text and images

contained in

this online exhibit are intended for personal research purposes only,

and are not to be otherwise reproduced without permission. To purchase a copy of the booklet Molly Ockett,

authored by Catherine Newell and published in 1991 by the Bethel Historical Society, visit our Museum Shop page.

and are not to be otherwise reproduced without permission. To purchase a copy of the booklet Molly Ockett,

authored by Catherine Newell and published in 1991 by the Bethel Historical Society, visit our Museum Shop page.

Learn more about the history of the Bethel area by browsing through

online articles from the Society's print publication, The Courier, or visit The Bethel Journals,

a website devoted to Bethel's past created by Society past president Donald G. Bennett.

Close this window.