New Towns Along the Androscoggin

The permanent colonial settlement of the Androscoggin valley began in the 1620s at Brunswick and, not surprisingly, that community became the first incorporated town on the River in 1717. But it was not until the defeat of French Canada by the British in 1763 that the region upriver of “Pejepscot” was considered safe for the development of new towns. Thus it was that the first settlers in such places as Durham, Lewiston, Greene, Turner, Livermore, Dixfield, Rumford, Newry, and Bethel did not arrive until the 1760s and 1770s, just before and during the American Revolution. Although Shelburne, New Hampshire, was settled around 1770, most of the towns between that community and Umbagog Lake were not permanently inhabited by white people until the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

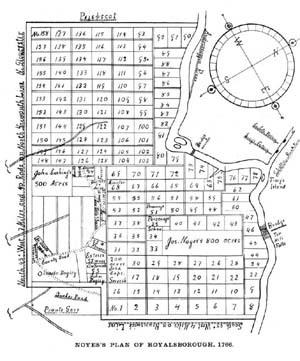

The published histories of these towns indicate that many were granted to people of influence who had little, if any, interest in relocating to the “Androscoggin country,” a term frequently applied to the upper valley in old documents. These absentee landlords, some of whom received grants as payment for military service during the French and Indian wars, hired surveyors to create town plans divided into grid patterns of roughly 50-acre parcels that virtually ignored the local topography—except when it came to the nutrient-rich intervales along the Androscoggin. Anxious to take advantage of the agricultural and forest wealth of this newly-opened territory, the hardy settlers (many of whom were from northern Massachusetts and southwestern New Hampshire) purchased farmsteads from the town proprietors or, in some cases, were given land in an effort to meet certain grant stipulations. It’s worth noting that the migration of people into the middle and upper Androscoggin valley was slowed but not halted by the Revolution, although an August 1781 Indian raid—the last in New England—on the towns of Newry, Bethel, Gilead and Shelburne produced tensions that lasted until the close of the War two years later.

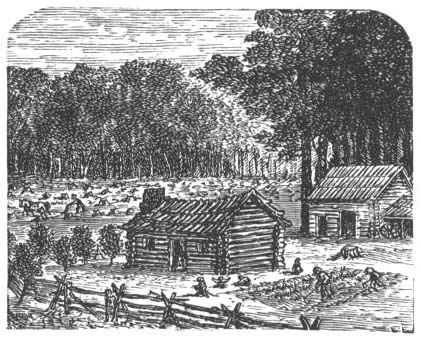

The 1760s and 1770s witnessed the clearing of land and the construction of farmsteads, houses, mills and churches as white people moved up the Androscoggin River to occupy territory long occupied by the Abenaki.

Arranged in a grid-like pattern, with the Androscoggin River on the right, this 1766 “lot and range” map of Royalsborough—incorporated as Durham, Maine, in 1789—clearly shows the narrow “intervale” lots bordering the River’s western bank. As in other towns throughout the valley, these fertile and oft-flooded parcels were much sought after by the first white settlers.

A series of relatively level uplands running alongside rivers and streams in the Androscoggin watershed were utilized for the location of roads as towns developed and prospered. The top photo shows a section of present-day Route 2 west of the village of Hanover, as it looked in the winter of 1910-11; the bottom photo was taken in Bethel about 1990 near the junction of Route 2 and the Sunday River Road (the Androscoggin appears on the right).

During the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, inhabitants of valley towns cut ice on the Androscoggin River for use in preserving foods during the hot summer months. Although ice-harvesting on the Androscoggin did not become of major commercial importance, as it did on the Kennebec, many farmers supplemented their yearly incoming by selling large blocks of ice to their neighbors.

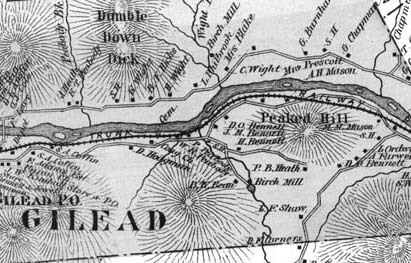

During the late 1840s and early 1850s, the Androscoggin River valley from Bethel, Maine, to Berlin, New Hampshire, was chosen as the best route for a railroad linking Portland with Montreal. This 1880 map (section) of Gilead, the next town west of Bethel, gives an idea of how tightly the railroad and road (now Route 2) were squeezed between the river and the mountains in this district.